“My mind is very visual: I can see anything in pictures, and I always visualize things. I can’t help it. It’s how I’m wired. So whatever you talk about, I’ll see pictures in my head. Very vivid, colorful, lifelike pictures. They aren’t still pictures. I can make them move. Reality, fiction, whatever. I really have to pull it back in to get focused. It was also a problem in the classroom because I’d sit there and imagine where I’d want to be, and what I’d want to do, and what I wanted to become, and I’d think happy thoughts, and I’d just be tuned out the whole time in class.”

“My mind is very visual: I can see anything in pictures, and I always visualize things. I can’t help it. It’s how I’m wired. So whatever you talk about, I’ll see pictures in my head. Very vivid, colorful, lifelike pictures. They aren’t still pictures. I can make them move. Reality, fiction, whatever. I really have to pull it back in to get focused. It was also a problem in the classroom because I’d sit there and imagine where I’d want to be, and what I’d want to do, and what I wanted to become, and I’d think happy thoughts, and I’d just be tuned out the whole time in class.”

– dyslexic CEO Glenn Bailey

Does this sound like you or does this not sound like you?

Having spoken to people with very vivid imagery like this and others who say they have no imagery at all, it’s surprising that more research into the process of mind wandering or daydreaming hasn’t been done up to this point in time.

Brain researchers now know that mind wandering is an active process of the brain rather than a passive loss of focus. As the mind wanders, it drifts away from any task at hand.

The brain centers associated with mind wandering are part of the default mode network, an area of great interest in those also studying creativity.

From Cerebral Cortex 25:3502-3514: “we found that connectivity between multiple reading-related areas and areas of the default mode network, in particular the precuneus, was stronger in dyslexic compared with nonimpaired readers.”

It is interesting to see that different research groups studying mind-wandering tend to take different positions as to whether mind-wandering is “bad” or “good. ” It looks bad if mind wandering is what study subjects are doing when their speed and accuracy of reading comprehension are being tested, but in fact, researchers have found that mind

wandering occurs often in their tests.

When people are asked, they will say they are thinking about their day, themselves, others, or what they will do in the future.

Mind-wandering is not just inattentiveness. It also seems to be important for certain types of problem-solving and creative thought.

Chicken-egg questions arise when thinking about the impact of mind wandering on reading comprehension.

Unsworth and McMillan (2013), for instance, found that mind wandering while reading is affected by people’s motivation to read, working memory, and the difficulty of text. Could dyslexics experience mind wandering because of the stress of text complexity plus working memory overload?

My goal is not to persuade you that reading is unnatural to dyslexics, but rather to raise awareness of how some dyslexic readers may struggle with over-active mind wandering with reading – especially it the text is difficult, there is lower motivation to read a particular text, and working memory could be overloaded.

On a practical level, if you are trying to help a student who seems to get hopelessly derailed when sitting down to read complex text, then try to prime the pump as much as you can before the reading is set to begin.

INVITE INTEREST

Try to pique curiosity or interest in a book by talking about it, raising a question about it, or reading the first chapter with plenty of emotion. As a group, dyslexics may have strong sensory imaginations when listening to exciting texts, so setting the scene can get a certain amount of momentum going so it’s easier to for the student to keep going with the rest of the text. Reading the first chapter also often identifies main characters and setting, reducing working memory demands when students encounter those names and words in the text.

LISTEN ALONG WITH READING

For students who are able to listen and read along at the same time, give that a try for reducing working memory demands while reading; it is not cheating. In fact, doing so can increase printed word recognition as well as reading endurance in general.

COULD STRONG DEFAULT MODE NETWORK ACTIVATION CONTRIBUTE TO THE LATE BLOOMING NATURE OF DYSLEXIA?

Answer: It certainly could! With what we know about dyslexia wiring, there is a bias toward long connections in the brain which could facilitate more unusual / creative ideas and complex thinking, but before maturation is complete, it also could put more demands on working memory and executive function. It should come as no surprise then that stronger default mode network activation (and therefore mind wandering) can make a linear progression through formal schooling difficult at best.

The purpose of sharing this scientific insight is to know what you’re dealing with, whether it’s you, your child, or your spouse (or all 3!). There is a lot that can be inconvenient about dyslexic wiring and parenting has more art about it than science. Knowing what to do and what not to do is a continuing challenge.

MIND WANDERING…THE USERS GUIDE

Some of you may recall that at one of our conferences on Dyslexia and Innovation, we invited a researcher to speak on Mind Wandering. Since that meeting, he’s added considerably more to the understanding of this interesting higher order thinking phenomenon.

Creative ideas of physicists and writers often occur during mind wandering and Schooler and his colleagues found that mind wander spells were especially fruitful for creatives who were looking to have a breakthrough in a problem they were working through.

Being aware of one’s tendencies to mind wander and how mind wandering can be used to work on problems can lead to greater productivity and less frustration.

Dr. Edward Hallowell, psychologist and author of Driven to Distraction has talked about his dyslexia as well as his ADHD. He likens ADHD to having a brain like a Ferrari race car engine – very powerful, but also potentially hard to stop (he imagines the Ferrari engine with bicycle brakes).

If we don’t see mind wandering in and of itself as a “bad” or deficit-type thing, really what we are trying to do is to learn how to control it – to use it when it will help us, but to keep in under control when we want it under control.

One non-medical approach to countering mind wandering is to develop a regular practice of Mindfulness. From Mindfulness Made Easy (from Ed Halliwell – not the same person!):

One non-medical approach to countering mind wandering is to develop a regular practice of Mindfulness. From Mindfulness Made Easy (from Ed Halliwell – not the same person!):

“In order to notice that the mind has wandered, and be able to return it to attention, there must be something bigger than that mind, a wider perspective that can observe the distraction. That wider perspective is awareness.

Awareness sees the whole picture. With it, we can experience life with a more open lens. We might think it’s a bad thing to notice the mind drifting, but actually the reverse is true. The fact we can see it means we’re opening to greater consciousness. It’s true that in mindfulness practice we’re cultivating a capacity to attend with greater stillness, stability, and strength.

But with awareness, we can discover a way of being that isn’t caught in the reactive jumble of thought, sensation, and impulse, even when attention is drawn to it.”

MIND WANDERING WHILE READING – DEEPER DIVE

But one thing that’s particularly interesting is a deepening in science’s understanding of the different types of mind wandering that exist while reading.

A nice overview of the scientific literature has come in a Frontiers in Psychology article (here).

Jonathan and his colleagues, for instance, have noted that some types of mind wandering occur with a subject’s awareness and at least partial control (“tuned out”), where as other events (“zoned out”) seem to occur with less awareness, surprising the reader once they have come to the end of a mind wandering episode.

How often do we consider mind wandering when students struggle with reading?

Probably not enough. We can sort through the possibilities by asking the student and trying to see if higher interest texts or priming the reading or even scaffolding improve understanding.

One study of mind wandering found the greatest extent of wandering occurred with listening; after that, was silent reading, and finally, the least mind wandering occurred when people were asked to read aloud.

One thing that these studies haven’t connected to, though is to what extent mind wandering is linked to personal imagery. A young student comes to mind who was seen our clinic. He was a bright and creative child with mild auditory processing difficulties, but also with strong imagistic thinking. He freely admitted that when he listened in class, they strongly evoked pictures – and then he could go off into daydreaming.

One thing that these studies haven’t connected to, though is to what extent mind wandering is linked to personal imagery. A young student comes to mind who was seen our clinic. He was a bright and creative child with mild auditory processing difficulties, but also with strong imagistic thinking. He freely admitted that when he listened in class, they strongly evoked pictures – and then he could go off into daydreaming.

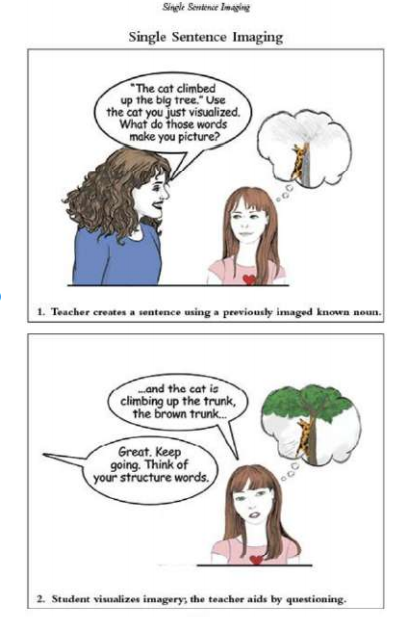

What turned out being a good match for him was Gander Publishing (Lindamood Bell’s) Visualizing and Verbalizing. The approach is fairly simple – accurate repeating back at the sentence level, then paragraph, page, then eventually pages.

What his tutor found out is that he had many false images triggered by listening or reading stories.

His mind wandering was not “off-task” in the usual meaning of the word. He was on-task, but once it hit his vivid imagining brain, the information was changed and his perception was no longer exactly what was heard or down on a printed page.

There is no magic with the Visualizing and Verbalizing curriculum. He just received regular practice in describing back what he had heard or read, improving his rigor of images, avoiding imagining what wasn’t actually said or heard. Ultimately, his listening became a little super power. He had disciplined himself to make accurate images of what was heard or read, and he did not have to take notes.

More recently, there has been a growing movement to include the positive sides of mind wandering and some creatives even recommend enhancing it – at appropriate times and for creative purposes.

From Fabry and Kukkonen’s Frontiers article:

“Based on the studies on relationship between mind-wandering and reading we have reviewed above, one might get the impression that reading is simply understood as the opposite of mind-wandering: on task, goal-directed and stimulus-dependent. There are many cases, however, in which reading does not have all these properties, which are worth considering in more detail. How often do we read a newspaper article with the intention to retain its main points in memory? How often are we just curious to check what it is about before we completely forget about it? Is our goal when we pick up Jane Austen’s (2008/1811) Sense and Sensibility to mine it for whatever information it holds about Regency Britain? Are we actually interested in tracing the intricacies of Austen’s plot? Aren’t readers rather looking for a kind of flow-state in literary reading that resembles mind-wandering in that readers detach their attention from the here and now?

In any case, as scientists and researchers debate the different applications and purposes of mind wandering and reading, teachers, parents, and readers of all sorts should do the same. What are we searching or hoping to instill in our reading?

The best answer is that we should have multiple purposes in reading – reading for enjoyment (Csikszentmihalyi’s flow), but also reading for information and reading for deep analysis (like dense literary texts or poetry).

Readers who have strong movies in their head when they read, may struggle putting their perceptions into words – whether aloud in a classroom discussion or down on paper for exams. Images by themselves can also invite false memories; these false memories can have creative benefits, but also penalize students academically when verbatim responses are only what are rewarded. Obviously, extremes of mind wandering and inability to mind wander are problematic; the challenge is finding the right balance and being able to create opportunities as well as some control.

In the video below, enjoy Dr. Michael Corballis’ suggestions for enhancing mind wandering and its positive aspects: