Recently I had such a nice visit to the Seattle Art Museum. It reminded me of how well dyslexic strengths can be cultivated in the multisensory experiences that are museums.

Recently I had such a nice visit to the Seattle Art Museum. It reminded me of how well dyslexic strengths can be cultivated in the multisensory experiences that are museums.

This past summer we had had a visit by Yuko Tsuji, a dyslexia advocate in Japan who spearheaded an effort to get Dyslexic Advantage translated into Japanese. The photo includes our son Krister, who is an artist and author illustrator of graphic novels.

I had seen that there was a visiting exhibit featuring Hokusai’s wood block prints at the museum.

MUSEUM VISITS ARE MULTISENSORY STORY EXPERIENCES

Today’s modern museums are rich multisensory experiences, with pictures and 3-dimensional works of every size and shape, and stories conveyed in pencil and paint, sculpture, and film. Museums introduce different lives, different cultures, and different visions.

Before we were let into the Hokusai exhibit, my artist son and I looked into the American wing.

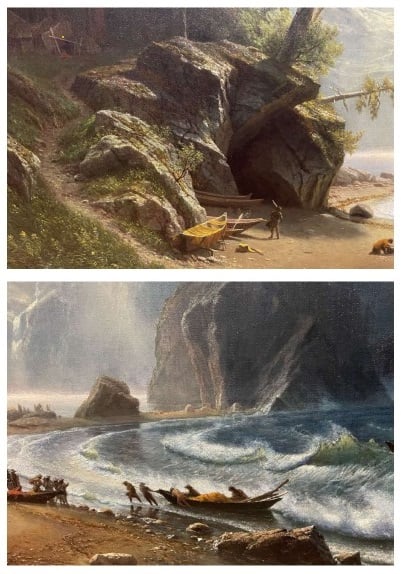

We saw this masterpiece, Puget on the Pacific Coast, by Albert Bierstadt.

If you’re in a hurry, you may walk by this painting without traveling ‘into it’ and seeing all the little stories and moments that it includes.

For instances, at the left, there is a simple shelter on the hill and below, boats where things (skins?) are laid out to dry. What is it that the figures on the right are laboring to bring in from the sea?

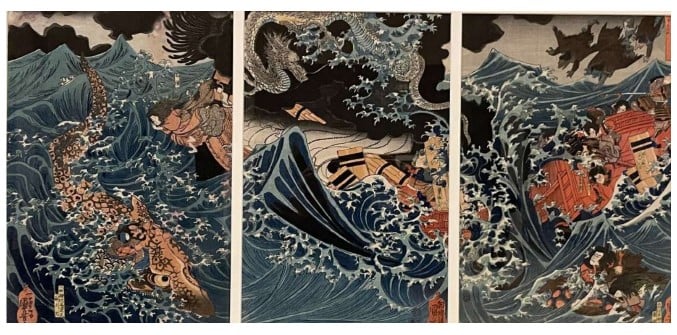

Hokusai print

Printmaking can present challenges for dyslexic and non-dyslexic students alike because the print process takes place ‘in relief’. Printer’s blocks need to be carved ‘in negative’ (that is, the parts of the block you don’t carve will show up in ink) and the entire image will be shown in reverse when it’s printed.

The ability to see ‘in reverse” is a strength for some dyslexic artist and printmakers, however.

In the educator tour, we first stopped in front of an animation of Hokusai’s pieces while the volunteer talked about his history and process, passed out samples of paper and reproductions of prints. When stopped in front of two large screens, the group was asked to compare the events between the two scenes, make educated guesses about what was happening and who the people were. The guide asked if we knew where we were ‘standing’ in the picture, for instance whether on level ground or looking down from a mountain, and plenty of time was given to answer questions. The art teachers in group shared how they could use simple supplies (like etching into foam core) to make prints.

It is easy to see how visiting a museum can be more exciting for a dyslexic learner than sitting with a book. You are that much closer to the people and things that are worth exhibiting and preserving in museums, and you can make strategic decisions and use creativity in sharing these precious things with others.

Many dyslexic people can excel in various parts of the museum industry; we previously interviewed Michael Graham who makes museum exhibits, and had museum directors Bill Brown (Whitney Museum) and Alexander Goldowsky (Boston Children’s Museum, MIT Museum) at past Dyslexic Advantage conferences.

In fact, one of the pioneers in children’s museums, Michael Spock, was also dyslexic.

“I didn’t read until the 5th grade. Even then, I couldn’t read or write in any conventional way….” – Michael Spock

When Michael created the Boston Children’s Museum, he was determined to make a museum for children that was more hands-on and exploratory. All museums today share to some degree in that innovation.

Although Michael struggled with reading, he also was curious and liked figuring out how things worked. As a result, all of the museums Michael worked on had lots of interactive exhibits and learning-play areas that really energized the museum industry.

Later Michael would reflect that he learned to “read the real world.”

If you haven’t visited a museum in awhile, check it out! Museums are great places for discovery and delight.