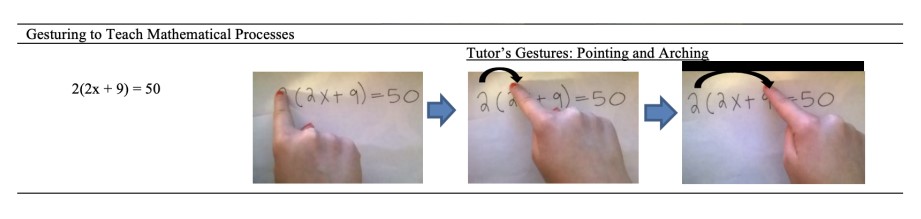

There’s an interesting paper by Hord and colleagues that showed how a secondary math teacher supported a student with LD and math anxiety using gestures.

Gestures can sometimes be used to help remember and retrieve math actions and relationships in long-term memory. Gestures are like kinesthetic activities in Orton-Gillingham / structured literacy programs..

Gestures can sometimes be used to help remember and retrieve math actions and relationships in long-term memory. Gestures are like kinesthetic activities in Orton-Gillingham / structured literacy programs..

One example of a gesture is using a twisting motion in association with multiplying by a reciprocal.

Here’s another gesture that a teacher or tutor can use when multiplying equations:

In the beginning, a student can work with color-coded arrows – but also air write over them before performing calculations; later when they encounter the problem on a test, having used such gestures can remind them of the spatial steps and sequence to solve the problem correctly.

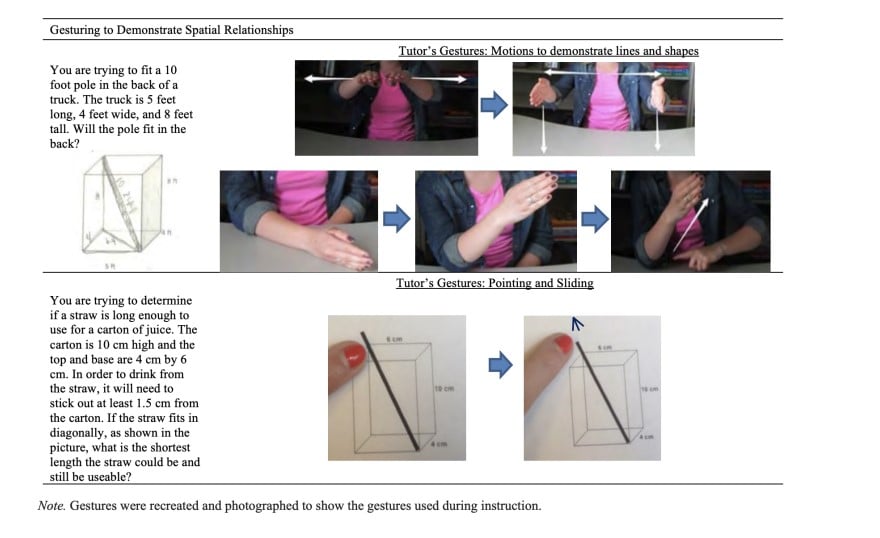

Another example using gestures is in a problem that requires calculating sides of shapes presented in 3 dimensions.

In the brief video below, a math instructors shows how gestures can be used to support math lessons.

Gestures may be especially helpful for dyslexic students because they may have strong mirror networks whereby they may experience a strong identification with movements that they observe. When math instruction is purely verbal, math learning is more dependent exclusively on verbal working memory – but verbal memory may be weaker than visual spatial working memory in many dyslexic students.

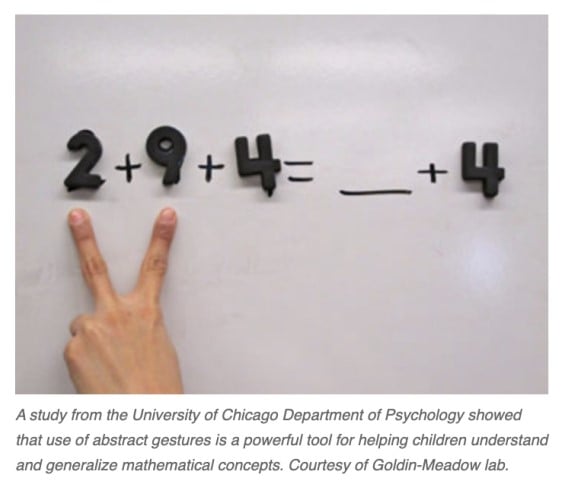

But among non-differentiated students, research suggests that the incorporation of gestures leads to more durable memories about procedures as well as generalization about concepts that can help students apply their knowledge in different problems.

As an example, as briefly summarized in an article in Psychological Science, researchers at the University of Chicago found that using abstract gestures to solve problems (for example in the figure, using 2 figures to group numbers), increased the likelihood that the students could generalize the knowledge to other contexts.

Research from the University of Iowa suggests that when a teacher explains a math problem verbally with appropriate gestures, they help students with strong verbal working memories, but also those with strong visuospatial working memories. When explanations were made with words only, students with stronger visuospatial memories got left behind.

Two other helpful articles on gesturing while teaching can be found here at Edutopia and here in the Wiley Online Library. Some gestures involve pointing, looking, and airwriting over relevant parts of problems, while other gestures are more representational – like making an exponential curve in the air when saying growth was exponential, or modeling atoms moving with hands.