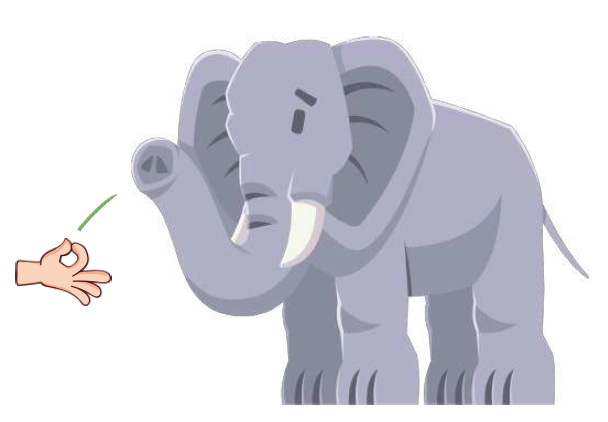

Don’t restrict students to decodable readers. It’s a little like trying to feed an elephant one blade of grass at a time.

Don’t restrict students to decodable readers. It’s a little like trying to feed an elephant one blade of grass at a time.

Reading decodable books has an important place in structured literacy programs for dyslexic students, but recently some in the reading community have been calling for “phonics-only” or “phonics-first” and this is not a good idea.

Recently Emeritus Literacy Professor Timothy Shanahan from the University of Illinois at Chicago has also called these policies as overreach. From his recent blog post:

“The National Reading Panel report (2000) is oft cited as the major support for phonics instruction. We found (I was a member of the panel) that explicit, systematic phonics instruction helped students to become better readers – based on a meta-analysis of 38 studies. But most of those studies provided the phonics instruction embedded in or accompanied by a more comprehensive reading program (the same was true of all the other components of reading that NRP examined). If you have any doubts, Linnea Ehri, the scientist who led the alphabetics part of the effort, has focused her research not only on how kids learn to recognize words (ever hear of “orthographic mapping”?), but also on more comprehensive approaches to decoding like Reading Rescue.

The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development found that once instruction had successfully raised kids to average levels of decoding ability – levels that should have resulted in successful reading – more than half the students still struggled. Decoding was essential, but insufficient for success.

That’s why Reid Lyon, Jack Fletcher, Barbara Foorman, Joe Torgesen, and so many others endorsed more comprehensive approaches to meeting children’s reading needs (Fletcher & Lyon, 1998). They were quite explicit that the teaching of these components takes places simultaneously, not consecutively or sequentially. It would be cruel to put all the emphasis on one part of the process, while allowing kids to languish with the other parts (sort of like providing calcium by taking away the protein).”

Which brings us back to the elephant and the blade of grass.

I first heard of that saying when it came to gifted children. Betty Meckstroth (co-author of Guiding the Gifted Child), was talking about how gifted children can make connections about ideas and information that others might not know even exist. The situation fits so well with dyslexic individuals as well.

Betty: “Teaching those types of voracious minds in a regular classroom without enhancement is like feeding an elephant one blade of grass at time. You’ll starve them.”

Dyslexic students are often very curious and hungry for information – and yet they can’t easily access the information they seek by reading. They may be trapped in classrooms below their intellectual level because of their reading and writing issues- but then get further stymied by well-meaning teachers and librarians who redirect them from above-reading level texts.

DECODABLE TEXTS AND ABOVE-LEVEL TEXTS

The truth is there are places for both decodable and above-level texts for dyslexic students. Decodable texts are motivating for students and they reinforce lessons.

Students realize what they are accomplishing as they move through stepwise curricula.

It’s the above-level texts though that attracts many to become lifelong readers. Students often have to be past a certain level before they can really enjoy it – but don’t underestimate the will of some students to get through texts that they really and truly want to read.

Although a rarity among the students we saw in our clinic, we would occasionally see students who were trained to read almost exclusively with decodable books.

These students were able to decode at the single word level, but struggled reading with any kind of fluency. They read slowly, one word at a time.

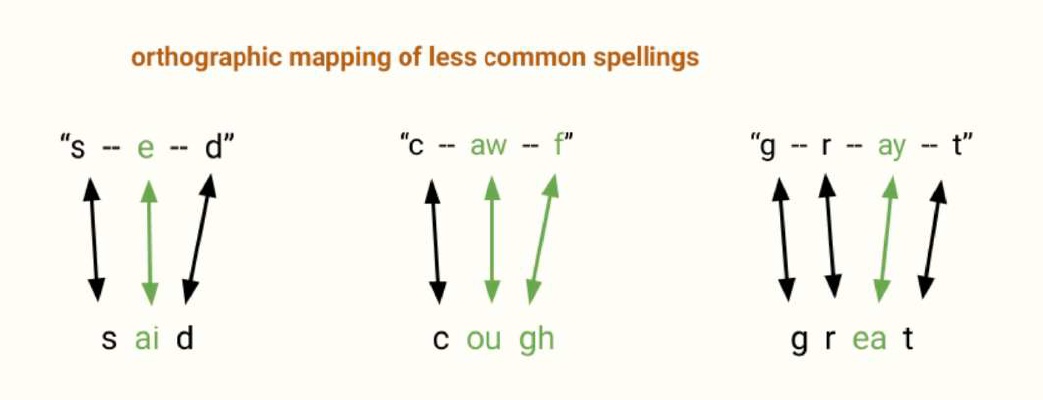

As we looked into the sources of why long words were so difficult, we found mixtures of difficulties – insufficient practice with decoding long words, lack of a personalized approach to orthographic mapping, or the visualization of letters and letter patterns to spell words. In orthographic mapping, students learn patterns that may occur commonly in words (for instance -igh, -ough, or -alk), but don’t have a 1:1 correspondence of letters to sounds.

In some cases, it was that students didn’t yet progress far enough in their structured literacy curriculum, or the curricula that were chosen had insufficient practice for them to learn.

Students who can get hooked on books above their reading level, may learn to recognize words by regularly checking words with an app-dictionary, listening to book audio while reading along, or even googling words that they cannot decode on their own. There are positive skills that can develop from such practice that would not take place if simple decodable readers were all they were permitted to read.

Like a healthy diet, having different types of reading is a good idea for young readers.

Reference: Doyoureadme.ca from an article on Orthographic Mapping