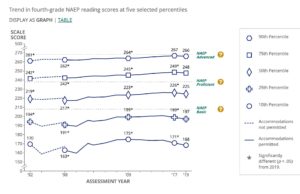

“Over the long term in reading, the lowest performing students – those readers who struggle the most – have made no progress from the first NAEP administration almost 30 years ago…”

There are discouraging reports from the 2019 NAEP Reading Assessment. NAEP stands for National Assessment of Educational Progress. Look at the reading assessment scores of 4th graders from 1992 to 2019.

Almost across the board, scores are down from 2017 to 2019.The lowest performers (NAEP Basic) are reading at even lower levels than their classmates from 2019. What’s going on?

Battles continue to rage about appropriate reading interventions for students. For families with dyslexic students, the statistic about how reading scores for the weakest readers haven’t improved over the past 30 years is shocking considering the advances in our understanding of dyslexia and the demonstrated benefit of targeted intervention.

Why are dyslexic students not receiving appropriate intervention in public school?

MOST DYSLEXIC STUDENTS AREN’T IDENTIFIED

Dyslexia is often missed in classrooms. New legislation and clarifications by the Department of Education have made it more likely that dyslexia will be recognized as an entity in schools; however, few schools conduct universal screening and many students can hide or compensate for their difficulties well enough that they aren’t recognized as having problems.

Even with states passing “early screening” laws, these screening exams (taking 1-8 minutes) are screening for important skills such as phonological awareness, but they aren’t screening for dyslexia. Some benefits come from being identified as having a need for phonological training, but because dyslexia is much more than reading, lack of formal identification means these students won’t be recognized for necessary accommodations, reading, writing, math, and foreign language supports, and differentiation of their curriculum in the event they are also highly intelligent.

EVEN IF STUDENTS ARE KNOWN TO BE DYSLEXIC, MANY MAY ONLY RECEIVE “PHONICS-LITE” CURRICULA

Recently, one of the most influential reading teachers in the country, Dr. LucyCalkins of Columbia Teachers College published published an open letter, No One Gets to Own the Term, ‘The Science of Reading, which seemed to be pushing back at the notion that curricula that she developed as part of “balanced literacy” is unscientific, or at least not keeping up with advances in the science of reading.

THE NAMES ARE CONFUSING, BUT BALANCED LITERACY IS ‘TYPICAL LITERACY’ WHICH EMPHASIZES AUTHENTIC BOOKS OVER INTENSIVE PHONOLOGICAL REMEDIATION

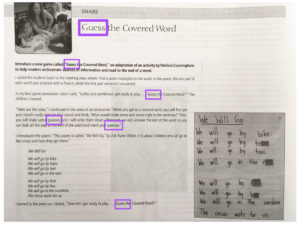

If your dyslexic students are in public school, it’s best to be aware of these issues because your students may be encouraged to “guess and go” rather than being given explicit instruction and practice breaking down down words in order to decode them. This may be because the teachers trained in the balanced literacy approach may put greater priority on learning to read from “authentic texts” rather than decodable readers (books that only contain words that students have learned to decode on a phonetic basis).

Experts are challenging (in both nice and not-so-nice ways) Dr. Calkins’ position that balanced literacy (including her own curricula) are keeping up with science.

At Reading Rockets, Martha Goldberg recently reviewed some of the lessons taught to teachers at one of the training institutes at Columbia:

“Our trainer frequently used the word “guess” to describe what good readers do. Your programs, Units of Study for Teaching Reading and Units of Study for Teaching Phonics, use that word as well received. ”

“Most primary teachers when asked if they teach phonics are, in my experience, likely to say, “Yes.” However, when I visit some of those classrooms, what they mean by phonics is pretty pale and thin; often no more than marking up a worksheet. Bloodless teaching not likely to help kids to figure out the decoding system.

When teaching the simple sound-symbol correspondences, teachers should make sure the kids can hear those sounds and distinguish them from other sounds; they should make sure kids can recognize these letters within words; they should make sure the kids can sound out unknown words or even nonsense words using those correspondences; and they should be able to read and write words with those elements, too.

Showing kids a spelling pattern and its pronunciation is a necessary step, but it’s not sufficient, if the goal is enabling kids to read and spell. Phonics teaching should provide opportunities to decode and spell words, to sort words, to recognize misspellings, and to gain proficiency in using all this information.

Although the numbers of phonics skills to be taught is usually pretty limited, the amount of phonics instruction kids should be receiving is considerable. Experts usually recommend 20-30 minutes or so of daily phonics instruction in grades K-2 (in other words, about 200 hours of such teaching). That means there is a need for thoroughness and depth; we want mastery, not familiarization.”

The teacher who I mentioned earlier, the one who may be doing no more than having kids mark up the daily phonics worksheet, can honestly say she is “teaching phonics,” since those lessons are being dispensed.”

From Reid Lyon and Vinita Chhabra about the science of reading:

“The majority of children who enter kindergarten and elementary school at risk for reading failure can learn to read at average or above-average levels—if they are identified early and given systematic, intensive instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics, reading fluency, vocabulary, and reading comprehension strategies (Lyon et al., 2001; Torgesen, 2002a). Substantial research carried out and supported by NICHD indicates clearly that without this systematic and intensive approach to early intervention, the majority of at-risk readers rarely catch up. Failure to read by 9 years of age portends a lifetime of illiteracy for at least 70 percent of struggling readers (Shaywitz, 2003).”

Margaret Goldberg again:

“Some struggling second grade readers will quietly flip through books during independent reading, but others quickly grow bored. More than once, I’ve seen a child throw a book bin and shout, “I hate these stupid books.” There’s no convincing an eight year old that his Level C books aren’t stupid.

Children who struggle with reading realize something many adults do not understand– they do not learn to read by reading. Desire to learn and time to practice are not sufficient for most students. They need to be taught how to read. I began to question why we prioritize independent reading in our instructional minutes when I saw beginning and struggling readers sitting alone with books, waiting to be taught.”

These scenarios may seem all too familiar, unfortunately. In the past few years, dyslexia groups like Decoding Dyslexia have made dramatic inroads into educational policy. Laws have been passed in an overwhelming majority of states, but then comes the slow process of forming committees, deciding on curricula, training teachers, and so on. Confusion and ambiguity over what level of rigor in decoding instruction is needed for students makes it less likely that students who need such instruction, get it.

In 2016, Martha Youman published a helpful review matrix of multisensory structured literacy programs, but there are no plans to update it and many valuable curricula are missed. The quirky “What Works Clearinghouse” is not a good resource for reviewing dyslexia curricula; the approval process is opaque and at least some reviews don’t seem to have a first hand knowledge of teaching students with dyslexia.

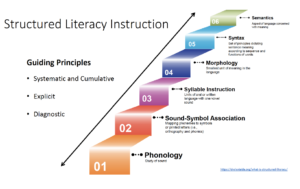

Understanding the different components of curricula are important because some programs are appropriate for general classroom students, whereas others are intended for students with moderate to severe dyslexia (Tier 3 in the RTI system).

Most strong school districts have access to multiple reading curricula; if a student isn’t showing progress, another curricula with additional supports may be indicated or existing curricula may need to be modified or supplemented.

In the figure below, see the different components of structured literacy, the gold standard for dyslexia remediation. Is your dyslexic student a fluent reader? If not, they may need targeted remediation that involves all the components listed below and immediate feedback for errors when they occur. Students may still listen to books at home and use audiobooks for content – it’s just that it should never be assumed that dyslexic students will just “pick up reading” by having them read more. Explicit incremental multisensory instruction unlocks the code for students and it’s worth fighting for.

Read more about structured literacy from the IDA: https://dyslexiaida.org/what-is-structured-literacy/