From our recent virtual lecture for the Hamlin Robinson Speaker Series, here are a few questions from viewers:

From our recent virtual lecture for the Hamlin Robinson Speaker Series, here are a few questions from viewers:

QUESTION: How do you separate vision processing disorders from dyslexia? How do you think about these? Also same with auditory processing disorders like CAPD?

ANSWER: It sounds as if you are well-informed about the fact that many individuals with dyslexia have visual and auditory processing disorders. Depending on how an individual is assessed, for instance by a medical professional, language specialist, vision specialist or auditory specialist, different “labels” can be attached to what may present as difficulty with visual aspects of reading or with hearing all of the sounds in words or in noisy environments.

On a practical level, integrating a wide range of test-related information along with a given client’s symptoms and difficulties is what medically-trained dyslexia professionals do as part of their clinical assessment. What are the practical implications of various test findings? In one case, visual processing difficulties may be mildly abnormal, but more significant difficulties are found in auditory processing; in other cases, the reverse may be true. In still other situations, the problems may be more related to memory-related challenges associated with dyslexia. All that said, there are many medical professionals who don’t receive adequate training in dyslexia – and many dyslexia specialists who don’t have medical backgrounds to interpret visual or auditory processing tests. Parents can read up on various possibilities, but they won’t have the clinical experience of seeing a wide range of individuals with dyslexia, knowing what happened with various interventions and seeing how things change over time.

With this context, it’s important for whoever is guiding an individual’s educational plan to know all potential issues – but also prioritize what is impacting education the most.

If a student is failing to make progress with dyslexia intervention because of more severe auditory or visual difficulties, then those problems may need to be specifically addressed to see if it affects reading.

If visual or auditory processing difficulties are mild and a simple treatable intervention like glasses or treatment of an ear infection are not necessary, then specific intervention may not be necessary other than some consideration of how these difficulties might impact reading instruction (for instance, read with a larger font, reading ruler, slower pronunciation of sounds, etc.).

When a student is planning to take high stakes tests like college entrance exams, or later in adulthood, licensing exams, then being aware of needs like visual processing – that may have an impact on time or the need to write in a test booklet instead of scantrons – is important.

QUESTION: How can we nurture Dyslexic strengths in our children?

ANSWER: There are many great challenges facing the nurturing of strengths in dyslexic children. Some of the challenges are external because traditional school work may provide little outlet for dyslexic strengths. Typically students who are struggling with school tasks often spend extra time receiving remediation with little time for extracurricular activities that allow them to develop or show their strengths.

Parents and teachers have an important role to identify strength and interest areas of their dyslexic students and make the time even in the midst of a busy school year. It’s my intent with every single issue of this newsletter or our Premium magazines to highlight how dyslexic strengths may present. We now have over 140 issues of these newsletter or Premium magazines – and they are all telling the stories of dyslexic strengths in various forms. Also listen to interviews and see various people found their strengths as children or adults. These strengths tend to recur and if there is no time for children to explore and live all types of experiences, they may never discover their true potential.

One homeschooling parent of 3 dyslexic children who have won multiple science fair awards at the state and national levels told me that she and her husband set out to have their children’s education reflect a 2:1 ratio of strengths to remediative work. Not everyone will be able to do that – but it’s an approach that has certainly worked for them. The actual numbers don’t matter and they are likely to change at different times, but the important thing to remember is that a student’s strengths are usually much more important than weaknesses – so making the emotional health of the student, it really sets them on a positive track for their future.

QUESTION: Clearly the dyslexic person has advantages in brain functions. But, they have to operate in a world that is not oriented to the way they think. They still have to read, write and compute. In addition, at this time they must also be able to see and understand complex information. How do we help them develop the skills they need while not diminishing their strengths?

ANSWER: This question is a bit related to the previous one – but I will add that it also raises the issue of the challenge that some dyslexic people have communicating their ideas to non-dyslexic co-workers or employees. The issue comes up quite a bit in workplaces especially when people have to work in teams.

For the challenges, dyslexic people do benefit by intervention, remediation, and assistive technology, but even so, there are many examples of people who found success at what they do despite not having received appropriate remediation. It is not impossible, but the overwhelming evidence is it that it is helpful for the vast majority of children – so that is why it is recommended and supported.

So all this being said, I don’t think intervention is “enough” especially if we want to do the best we can to supporting young people. Talent and strength development has always been important for parents who have the means to help their children – and that help can take many forms.

I like the fact that you mentioned the ability to see and understand complex information. There are significant numbers of dyslexic students who have advanced conceptual ability (i.e. “gifted”) in addition to their dyslexia. For these students, having advanced curriculum with the use of assistive technology and accommodations when necessary can be their best fit in the educational system.

Too often after formal testing, attention is driven to the weak scores, with little thought for the strengths. Does the student look forward to something during their school day? Are they exercising their creative minds and their advanced conceptual thinking? Over the years, we’ve heard about some kids flourishing after winning one of our Karina Eide Young Writers Awards, or others from out-of-the-box choice of what to do on their summer vacation.

We’ve known many kids who were grades behind in reading and writing, who nevertheless talked with their parents on every topic under the sun. They discussed TED talks, talked to relatives and various family friends about their interesting occupations, and they explored subjects and fields beyond their grade school curricula.

As we’ve begun putting together some of the updates for the 10-ish year anniversary of Dyslexic Advantage, it’s even clearer that what we know about dyslexic differences should imply more learning based on physical experiences that employ personal or episodic memory.

It is also important for dyslexics as a group to learn about their differences and develop strategies for communicating their thoughts to the non-dyslexic world.

In the best of all possible worlds, non-dyslexics should work just as hard at learning how to communicate effectively with the dyslexic world.

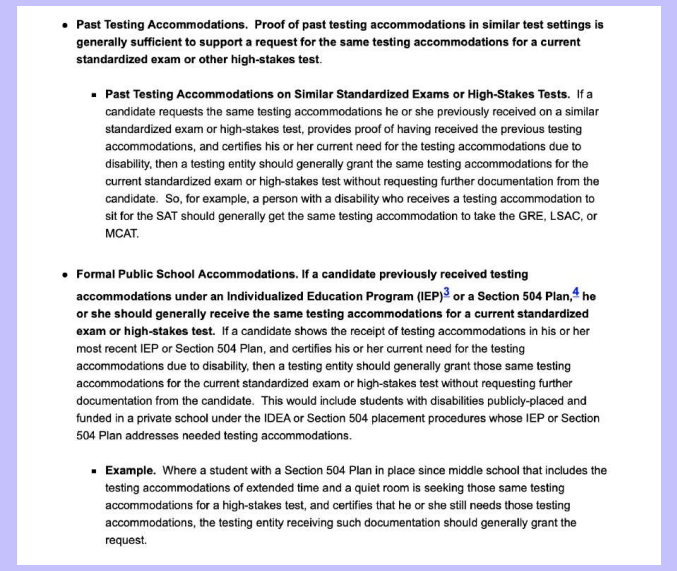

QUESTION: I’d like advice on what to say/do when a school/program requests further testing on a dyslexic as testing is expensive and time consuming, and dyslexia does not go away!

ANSWER: This is can be a very frustrating and costly problem.

As you may know, the Department of Education tried to clarify this issue and not require families to undergo continue with frequent burdensome expensive re-testing for learning disabilities.

A summary post is located HERE. The government document is HERE. The relevant section is below.

Students with an IEP may qualify automatically for college entrance accommodations. 504 or other students may be on the edge; if they “get by” without accommodations in school, it is harder to justify that they need accommodations for high stakes exams. But it is also true the the demands of college-level reading and writing are also much greater.

Professionals who know your student may try to appeal to the College Board stating that repeat testing is not necessary. In general, we have heard that more than half of appeals tend to be granted, so it’s always worth trying.

Present your case like a lawyer, collect letters of support from teachers and other professionals who know your student. Sometimes universities have a pro bono (free) special education law clinic who will give you advice for free or on a sliding scale that can strengthen your case.