When I heard that what’s been called America’s Stonehenge, Opus 40, was hand-built by a dyslexic artist, I wasn’t really surprised. A lot of dyslexics are grand slam-type creators.

When I heard that what’s been called America’s Stonehenge, Opus 40, was hand-built by a dyslexic artist, I wasn’t really surprised. A lot of dyslexics are grand slam-type creators.

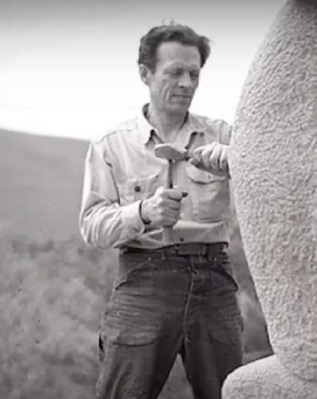

Harvey Fite spent half his life creating the Opus 40 Sculpture Park. He hand cut and place all the stones in his sculptural landscape. Architectural Digest called it one of “the most beguiling works of art on the entire continent, while The Art Newspaper called it “a testament to the wondrous and crazy things humans can create.”

Harvey had a non-linear path to his goal.

His father was a carpenter and his family was frequently strained financially. He intended to become a lawyer, but dropped out, briefly tried divinity school, then found himself in the Woodstock area having joined a theater group. While waiting backstage, he picked up a wooden spool and began carving.

He became so interested in carving, he left theater and began living in the barn of one of his former professors at Bard College. He was ultimately asked to create a Fine Arts department at the college, then affiliated with Columbia University. He then traveled to Italy to study stone carving.

In 1938, in search of stone for his sculptures and a place to live, he bought twelve acres for $376.25 and began shaping the land and the stones themselves.

See more beautiful pictures of Opus 40 HERE and Hudson Valley Explored.

In 1939, Harvey got invited to travel to Honduras to do restoration work on Mayan sculptures. He became fascinated by how the Mayans used stone masonry to develop structures with plazas, stairs, and terraces and how they worked with the natural topography of the landscape. The “dry key” approach used large key stones to draw smaller surrounding stones to them so that stable structures could be built without mortar or cement.

His experiences led Harvey to use similar principles in Opus 40. He also emulated the Mayan tradition of making structures fit around natural features rather than the other way around. As a result, his fitted bluestones curve around quarry springs, trees, and natural shapes.

The striking monolith (picture below) that takes its place presented new challenges that Harvey had to solve…like figuring out how to position the 9 ton rock into place.

Harvey ended up choosing an ancient Egyptian approach using wood blocks and a truck, winch, and wire to raise the stone into its final position.

Harvey’s dyslexia story is being pieced together by his stepson Tad Richards who along with his wife Pat have been stewards of Opus 40 as well as putting together Harvey’s memoirs. I had the chance to talk with Tad and he shared the following with me about Harvey’s dyslexia…

Although Tad Richards grew up in Harvey’s household as his stepson, he never knew about Harvey’s dyslexia until he began reading his memoirs. He knew his mother read to his father aloud in the evenings, he “assumed that it was a loving companionable way to spend an evening (which indeed it was),” but he was to learn that reading difficulties dogged Harvey throughout his life:

“Harvey could not learn to read. Letters on a page made no sense to him. He sometimes memorized an entire lesson, getting his mother or brother to read it to him, or poring over it for hours, absorbing one letter at a time, painstakingly turning them into words.”

“Harvey can’t read, but he knows everything…”

– from Ralph Moseley, biographer of Harvey Fite, based on interviews of Fite’s friends.

As many in this community would be familiar with, Harvey was taken to a succession of eye doctors, had to listen to a series of inaccurate pronouncements (“it’s an illusion”), and criticized for poor work because his dyslexia had never been formally identified. Harvey may not have had the educational successes he had if he hadn’t been able to memorize as well as he could, get help from friends who helped summarize readings, or impress people on an individual basis with his knowledge and his ideas. In spite of it all, Harvey survived, thrived, and created his magnificent work of Opus 40.

Harvey might love to see what his hand-built monument has grown to today. In 1980, Richie Havens, a rock great known for his “Freedom” performance at Woodstock gave the first large public concert at Opus 40. Since that time, there have been many performances by legendary greats such as Sonny Rollins or Orleans. Jazz great Sonny Rollins said that Opus 40 embodies his Saxophone Colossus.

After Harvey and his wife passed, Tad Richards and his wife took over Opus 40’s stewardship, forming a non-profit charity to support it and more recently having it recognized on the National Historic Register. The National Register of Historic Places is part of a national program to coordinate and support public and private efforts to identify, evaluate, and protect America’s historic and archeological treasures. Kudos to Harvey and his family for creating his meeting place for generations to come.