This book has wonderful strategies and examples that will be helpful for many dyslexic actors and actresses, but also middle, high school, and college students who are tasked with reading complex texts.

Listen to my interview with Petronilla here:

“For me, as a dyslexic, Shakespeare is very accommodating. It has taken me eleven years of struggle to come to realize, because of my dyslexia, I understand things through image and metaphor. Shakespeare’s writing clicks in my head the way numbers click for a mathematician.”

– Fred, an acting student with dyslexia (from Teaching Strategies for Neurodiversity and Dyslexia in Actor Training

What I thought was especially wonderful about Petronilla’s accounts with her students is how she wasn’t satisfied with just giving the text to her students in advance or having a fellow student help with the reading, she learned about the benefits of multisensory learning, imagery, and movement for her dyslexic students and persisted with them so that they found their voices and methods of understanding and associating text so that the full glory of their performances could shine through. As a teacher assigned to teach classes in sight reading, she often quickly identified dyslexic students who would have trouble with standard instruction.

In Petronilla’s book, she talks about her breakthrough with a student, David, that led her to change her teaching practices and encourage her students to interact with texts and scripts in a way that built on their strengths.

From her book:

“I noticed a significant improvement in his grasp of reading when we had worked on a Shakespeare text using the Cicely Berry-inspired deconstruction methods; the whole class of students reading the text round in a circle, word by word, then punctuation mark to punctuation mark, then sentence to sentence. This helped break it down for him so he could get an overall comprehension of the piece…getting the words into his body/mind through physical actions meant that suddenly David could read for about a paragraph without stumbling, and therefore had more freedom to exercise his acting instincts….”

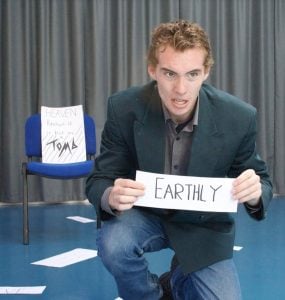

When David chose to act out Sonnet 17, he placed cards around the stage and acted out the text in choreographed physical movements. For instance, “when Shakespeare had used the word stretched, David had a folded-up card with the word stretched, penned in elongated print, which he gradually revealed, extending in concertina-fashioned pleats. The word heavenly was written on a sign placed upstage, and then when spoken, was held high above David’s head…whilst earthy was enacted downstage, on the floor….For the phrase hides your life, David had folded a piece of paper in two, with the word life hidden within it…the words beauty and graces were words that David felt were written from Shakespeare’s heart, therefore he decided to tuck them into his inner jacket pocket…”

When David chose to act out Sonnet 17, he placed cards around the stage and acted out the text in choreographed physical movements. For instance, “when Shakespeare had used the word stretched, David had a folded-up card with the word stretched, penned in elongated print, which he gradually revealed, extending in concertina-fashioned pleats. The word heavenly was written on a sign placed upstage, and then when spoken, was held high above David’s head…whilst earthy was enacted downstage, on the floor….For the phrase hides your life, David had folded a piece of paper in two, with the word life hidden within it…the words beauty and graces were words that David felt were written from Shakespeare’s heart, therefore he decided to tuck them into his inner jacket pocket…”

Petronilla’s study of metaphor generation and “embodied cognition” reminded me of the study by Kasirer and Mashal that showed that dyslexic adults had superior performances with novel metaphor generation compared to their non-dyslexic peers. No wonder there seem to be so many talented dyslexic poets and writers! We probably aren’t incorporating metaphors as much as we should in literature studies.

If you listen to my interview with Petronilla above, there are many interesting insights that she shares – for instance, one dyslexic student she discovered who could take notes well using the International Phonetic Alphabet or IPA. Unlike standard English, there is a one-to-one correspondence between letters and sound.

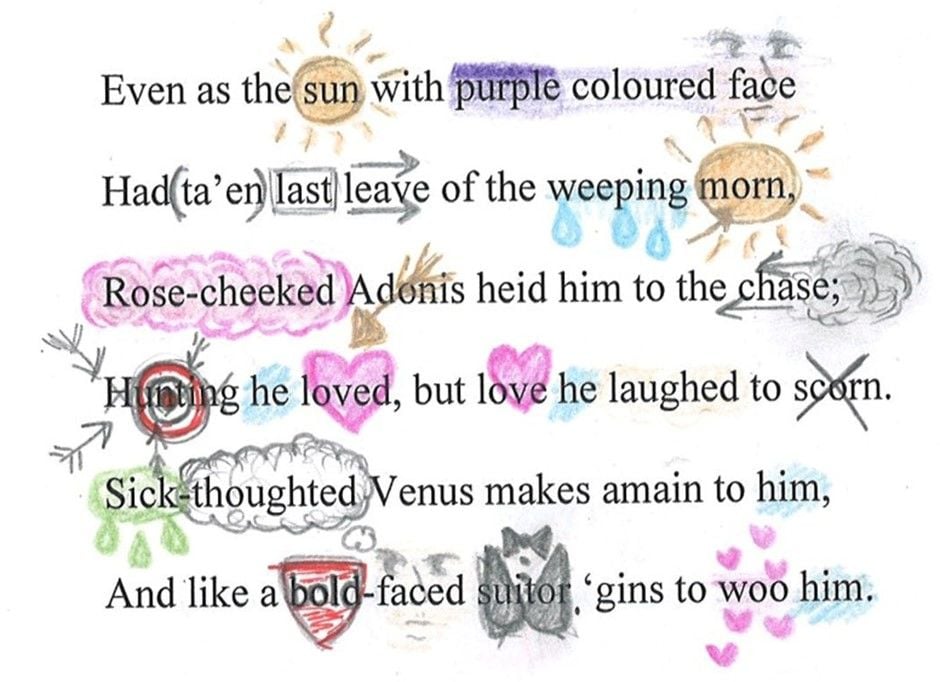

At left is one of Petronilla’s student’s visual storyboarding of Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis.

At left is one of Petronilla’s student’s visual storyboarding of Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis.

Purchase Petronilla’s book HERE.